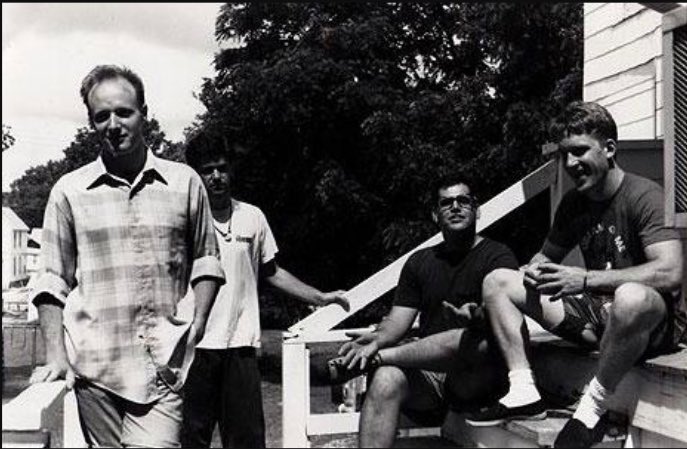

BILL STEVENSON

(ALL/DESCENDENTS)

[The "Lost Issue" -- early 1990s. Never published]

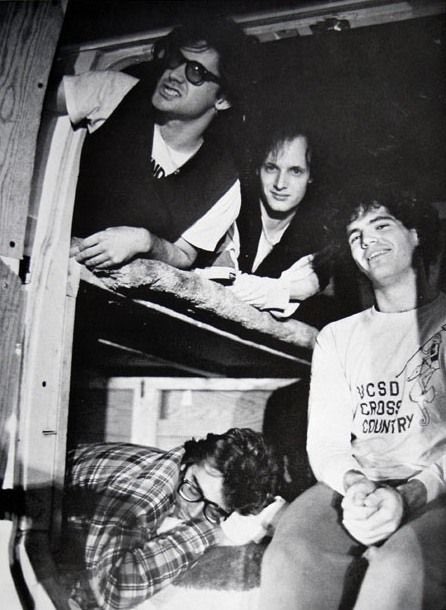

Traveling across the country, sardined in a dank, windowless van with six other men who haven't bathed for days would probably be as close to hell as most people would like to come.

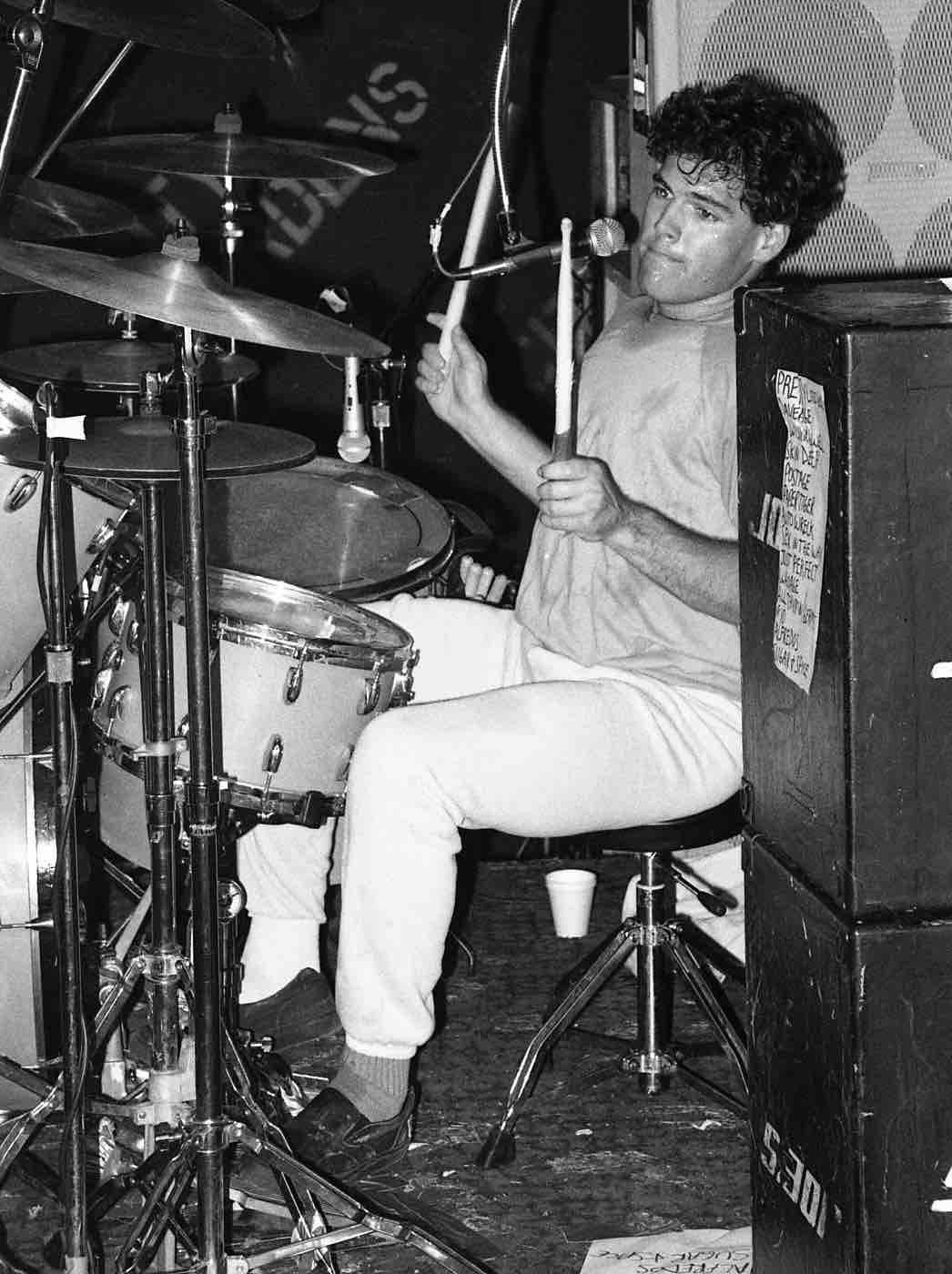

But for Bill Stevenson, drummer of All, it's been an annual ritual since the band was the Descendents back in the early 1980s.

For nine months each year, Stevenson, vocalist Scott Reynolds, Karl Alvarez, bassist for All, guitarist Stephen Egerton and various friends/roadies pile into the van and zoom onto the highways and byways to play shows in all corners of American Society.

"I can see people being turned off by it," Stevenson admitted. "There's long drives with junk food, unless you really go out of your way, because you can't really cook anything. You have to constantly drink Cokes and coffee, because you don't get lot of sleep."

For the most part, the tours have been successful for All, both logistically and financially, but tragedy does strike on occasion. It's a safe bet that few bands have experienced such heart-wrenching events such as a portable toilet overturning inside the van (as chronicled in the liner notes of All's live "Trailblazer" record).

For the most part, the tours have been successful for All, both logistically and financially, but tragedy does strike on occasion. It's a safe bet that few bands have experienced such heart-wrenching events such as a portable toilet overturning inside the van (as chronicled in the liner notes of All's live "Trailblazer" record).

The constant touring, though, has also taken its toll on the All family in other ways, most notably with the departure of underground veteran Dave Smalley, the band's first singer after Milo Aukerman left the Descendents and the band changed its name.

"It's sort of like being in the army with all of the touring and everything." Stevenson said. "It's not Dave's fault. I think people think, 'Oh, it sounds like fun.' And after a year or so of doing it, it might get in their blood, and they might really like it, or they might go, ‘Jeez, I’ve had enough.’

"The mechanics of a tour are pretty unfavorable to actually playing music, which is what you tour for, so I can see people being turned off by it," Stevenson said.

But for Stevenson, life on the road is just that: his life, and he wouldn't have it any other way.

"I'm not complaining about touring, but I value our music and I enjoy other facets of touring more than I hate the disadvantageous elements," Stevenson said. "Whereas, other people may like the music, but they're not committed to it, because for them, the bummers outweigh the good facets. I enjoy it. And besides that, they say investment determines interest, I've invested almost half of my adult life in it."

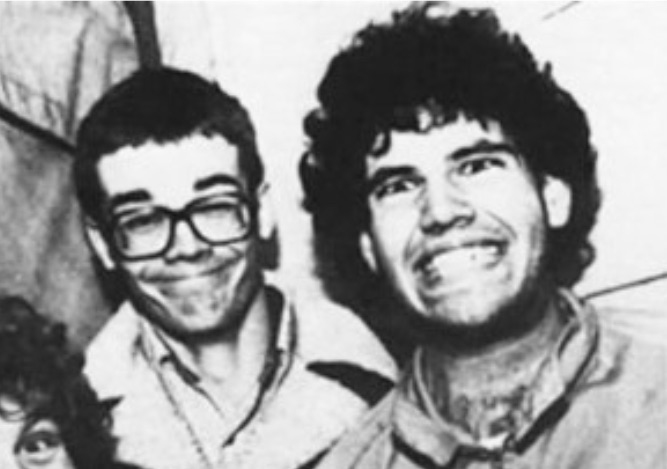

All's history goes back to Southern California where Stevenson, then 14 years old, got together with two high school friends in 1978 and founded All's precursor, the Descendents.

The three piece went through a number of trial singers until Aukerman, Stevenson’s friend, joined on.

The band continued with a steady line-up until 1984, when the band members spread out. Stevenson became the permanent drummer for punk legends Black Flag and Aukerman went to college in San Diego.

The band then reunited the following year, releasing “I Don't Want to Grow Up."

Stevenson and Aukerman parted company with bassist Doug Carrion and guitarist Ray Cooper, and brought Alvarez and Egerton on board.

The new line up released "All" and two live albums. Then Aukerman decided to leave the band to pursue a graduate degree in microbiology in the summer of 1987.

"Milo's my best friend ever in the whole world," Stevenson says. "He was really miserable the last few tours, so I'm really glad that he left. He just wasn't happy. Now he is happy, and me and him are very good friends like we used to be when we started the band."

With Aukerman's departure, Stevenson felt that change was in order.

Although All's recent work is definitely more varied than the songs recorded during the Descendents years -- slower, more complex melodies and "deeper" lyrics -- Stevenson said that the immediate course of action when the band became All was simple.

"We changed the name. That's all we did," Stevenson said. " 'All' is the best name you can have. It's the biggest word, the word with the most meaning in the English language.. . I've been wanting this name for eight years. This is such a fuckin' cool name. I couldn't get the other guys to go along with it, and then they finally did.”

But with the addition of Smalley, a veteran of the early-80s Boston hardcore scene, Washington, D.C.’s Dag Nasty and currently the singer for Down By Law, All's writing style began to shift.

"There's a certain singing style that he introduced into the group," Stevenson said. "It warranted a lot of harmonies, and not as an aggressive or loose or spontaneous approach. And that, to me, warranted a special production and a special harmony."

All's work recently has been catching the eye of those outside of the underground, with favorable mentions over the last couple of years by Spin and People magazine (yes, People.)

But Stevenson said that All is so inaccessible to the mainstream audience, that he's steering clear of the corporate record industry.

"I've had majors labels who have approached me, but they never approached with anything worthwhile," Stevenson said. "We're a far cry from direct pop music like Hüsker Dü or Soul Asylum. We're liable to release something with “Scratch and Sniff Shit.”

For Stevenson, it's a matter of artistic control, and he wants the freedom for All to write tributes to "sleeping, farting and food."

"We might just as well shit on the record as have a song about the bass we caught the other day or about the hair in the bathtub," Stevenson said. "A major label wants control of which songs are going to be on it or how they're going to be produced. They might even choose a whole other writer to write some or all of your music.

Stevenson said that money isn't an issue.

"The trade-off [in signing to a major label] is that you get serious bucks, man," Stevenson said. "I mean, we could plug right into marketable songs like 'She's My Ex.' I could write those songs all day, make a lot of money, have a nice tour bus, but what would be left of the music? As of yet, nothing has come to us which was reasonable in respect to our musical goals, which are totally fucking ludicrous. I'm surprised that anyone comes to see us play, because it's like we'll say, 'Here's a song about eating a hamburger.' "

Stevenson does acknowledge, though, that college radio stations have taken All's music to heart. But he insists it's by coincidence, not by intent.

"We don’t subscribe to the pop or college radio thing," Stevenson said. "College radio has always loved it, but that's their choice, not ours."

For Stevenson, one of the main reasons why he has probably been into the band so long is that he's been able to make changes to keep the creative energies fresh.

One of All's biggest step in keeping the quartet's music exciting was their recent move from Los Angeles to, believe it or not, Brookfield, Missouri.

"l decided we had to move for both financial and psychological reasons," Stevenson said. “I think L.A. was starting to have an effect. The area we lived in became infested with bands and alcohol and drugs. We rented one of eight small spaces in an office building, and lawyers were in the other ones. We'd practice at night after they had left. We were also sleeping in the back of it, but we didn't let anyone know.

But All's choice living/practice area took a turn for the worse. “Eventually, one by one, bands moved in and the lawyers moved out," Stevenson said. "This whole place became a sort of party thing, which is the exact opposite of what I had in mind. I wanted a place where we could practice and do our thing. So every day, people would come over and they would drink and screw and all of that. I think it was stifling our progress musically, so we moved.”

But to Missouri of all places?

"My father owns a house out there, which he rented to me at no discount," Stevenson said. "It's $350 a month for a huge house, where we all have our own bedrooms, and we have a decent office to run the bookings and everything to keep it all going smoothly. We have a kitchen and things like that which we never had before. We're paying one-fourth the rent we were paying in L.A."

But as All trailblazes into the 90s, Stevenson said that his whole attitude about the band is what keeps the music fresh and the whole experience exciting and adventurous.

"I guess that would get down to a basic work ethic," Stevenson said. "You have a pride in yourself and whatever you're representing yourself as. If you're a painter or a lumberjack, it's all the same. There is a certain pride in saying, ‘This is what I do, and I'm going to try and do the best that I can. Even if I'm sick tonight, or if I don't feel like it, or if I had a fight with my girlfriend, I'm still going to try and do my best.' "